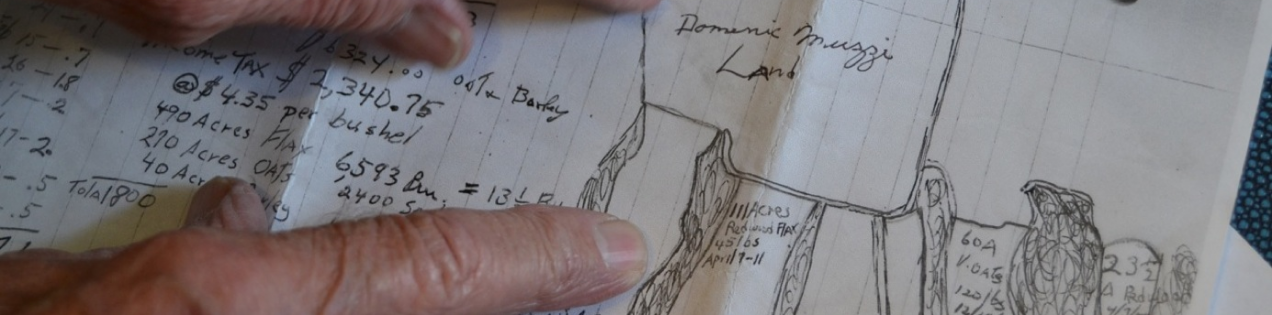

His ancestors relied on the 1840s Hawken muzzleloader to survive as they trekked from Missouri to California. It hangs above his fireplace. The deed is newer, but not by much. It’s a copy of the 1852 contract that awarded 800 acres to his family for $600 from Juan José Gonzalez, a Mexican landowner. Gonzalez’s wife couldn’t write, so she put an X for her name.

Moore’s family built the first wood frame house in what would become Pescadero, one of the oldest coastal towns in San Mateo County. His wife, Ruth, comes from the Steele family, which raised cattle in the 1860s near what’s now Año Nuevo State Park. The couple can narrate an almost unbroken string of names and dates, farms and ranches, booms and busts, from the 1880s onward.

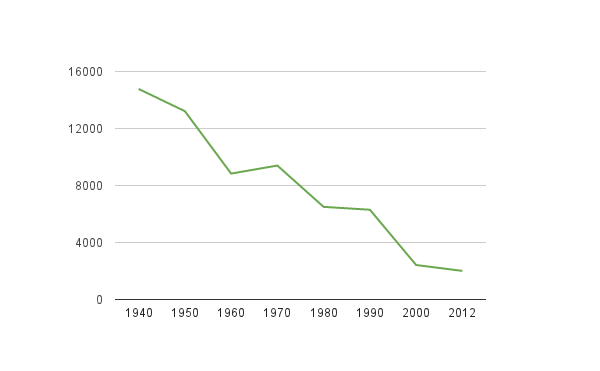

These days, they talk about far fewer farms and ranches, as decades of rising costs and plunging profits have made the vast acreage needed for cattle to graze too expensive for many ranchers.

“My ancestors bought 1,500 acres from Juan José Gonzalez for 26 wild cows,” Moore said. ![]() “My uncle bought the land for himself for $35,000 in the 1940s. My grandkids just sold it for $12.5 million.”

“My uncle bought the land for himself for $35,000 in the 1940s. My grandkids just sold it for $12.5 million.”

More money for less land has become a refrain throughout rural parts of the county, fueled by suburban growth and Silicon Valley prosperity east of the Santa Cruz Mountains.

Families that do own ranchland often sell rather than split a property among their heirs, seeing the cattle business as a financial impossibility.

Some private owners with large acreage will lease their properties for grazing, but others have fenced off their resident property for weekend getaways.

But a new dynamic has started to change minds in this age-old conversation about land. Conservationists, land managers and ranching families are working together, with a common desire to see the county’s rural landscapes preserved- even if they don’t always agree on how to do it.

What has united open space groups formed by voter referendum or citizen advocacy with ranchers and farmers who have long claims ![]() to the land?

to the land?

Cows.

In a policy change, many conservationists no longer view the cow as a scourge, and are actively promoting controlled cattle grazing on open land. For their part, ranchers from inside and outside the county are bidding on these new leases.

“Fifteen to 20 years ago, open space thought cattle were bad,” said Doniga Markegard, who ranches cattle with her husband Erik on land leased from both conservation groups and private owners. “Five years ago there was a big shift in that thinking. They saw that proper management of cattle can actually regenerate the habitat.”

The change of heart has come about as science, economics and necessity alter the debate.

As farmers and ranchers can no longer afford to buy land, and as San Mateo County and state regulators restrict much building development on agricultural land, open-space groups and wealthy private landowners are often the only buyers left who can purchase large acreage in the rural county.

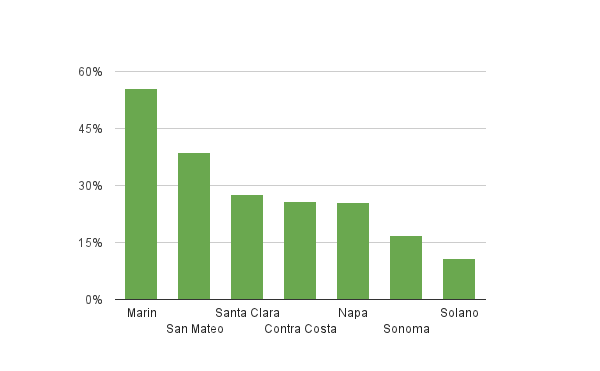

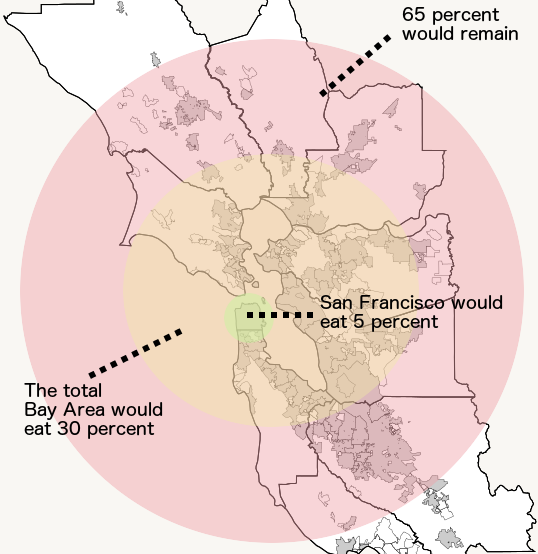

The increase, in dollars, of the price of one acre of agricultural land from 1997 to 2007, per county in the Bay Area.

But once the open space groups purchase the properties, they are faced with a dilemma: how to manage their holdings in a way that’s friendly to both the environment and their budget.

This is where cows come in.

Harnessing the grazing power of cattle herds and the management of ranchers, open space groups can remove invasive species such as non-native grasses, keep a watchful eye on their properties and help preserve a rural economy on Silicon Valley’s coast. On their end, ranchers can access large acreage that was previously off limits.

36,000

Many people involved in the process are cautiously optimistic that it is a way forward for the county’s small but tenacious ranching industry, and might mark a new start for the sometimes rocky relationship between conservation and agriculture on the coast.

CREDITS:

Top image:

Cattle graze at Driscoll Ranch.

Photo:

Steele Barn, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Historic American Buildings Survey.

Data:

Map data courtesy of the US Census Bureau, Google, and the US Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistics Service. Cattle statistic courtesy of Oregon State University.